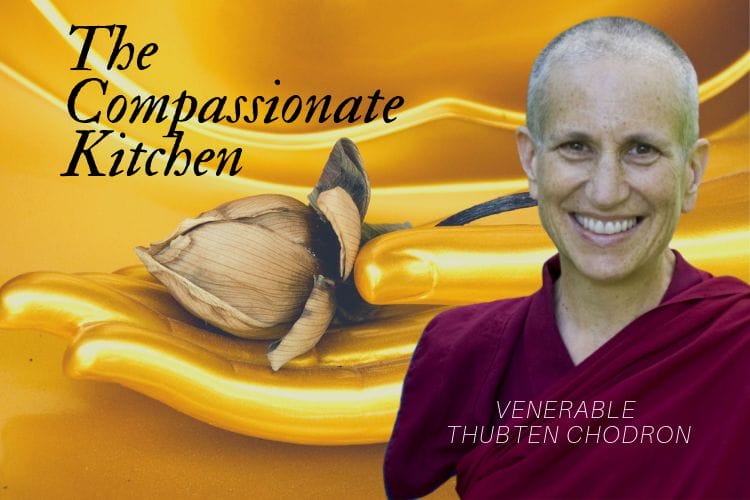

Thubten Chodron: The Compassionate Kitchen

If they would like to join, in supporting it, and miraculously, we were able to get the property and then pay off the mortgage. I think, due to the kindness of other people and the enthusiasm of other people because they had encountered the Buddhist teachings. They had found the teachings useful in their life, and they wanted to help start a monastery.

Sandie Sedgbeer: Reading your book, The Compassionate Kitchen, found HERE on Amazon, which I found interesting and enlightening, it seems to come across to me that you’re the kind of person who really likes a challenge. You pushed yourself all the way through to do things that perhaps are not expected.

I can imagine that you just trotted out, a very nice, neat explanation of how you came to find the abbey, but I’m sure it wasn’t that simple. It was such an intimidating undertaking must’ve had it some glitches.

Venerable Thubten Chodron: Yes, it did.

Sandie Sedgbeer: But even when you got the abbey, you then decided that you would challenge yourself even further by setting a goal that you were not going to purchase any food for yourselves but instead would be reliant on the generosity and offerings of others.

You tell in the book the story of the origin of the alms round or pindapata, where the monks would stand silently in front of a house with their alms bowl and await offerings, but tell us a little bit about that and why you decided to implement that at the abbey?

Venerable Thubten Chodron: When Buddhism began in ancient India, there had already been a culture of wandering mendicants, spiritual people, who went, who, when it was mealtime, went into the city with their bowls and people would support him.

This is part of Indian culture and Indian traditions. So, the Buddhist disciples did the same thing, and there are a few reasons behind doing this.

First, it makes you very, very grateful to other people, and you don’t take your food for granted. You really appreciate that people are giving you food, that they are keeping you alive by the goodness of their heart because they go to work every day and work hard to get the money or get the food, and then, they’re sharing it with you.

It really helps your spiritual practice because you realize that you have a responsibility to practice well, to repay the kindness that you’re receiving.

The second reason was to cultivate satisfaction or contentment because you eat just what people to give you. So, you don’t go and say, oh, you’re giving me rice. I don’t want rice. I want noodles, or you’re giving me that? It cuts out the pickiness and challenges us to be content with whatever people give.

So, you can see, because I had lived alone for a while, and had to go to the store to buy food, then, of course, I could get things I like and go to the store whenever I wanted. But none of that was good for my Dharma practice. So, in starting the monastery, I really wanted to go back to the idea that the Buddha had for his community.

And although we, it’s a little bit difficult in the US to go on pindapata, to walk with your alms bowl in town–we have some friends in California who did that. So, I thought the best way to do it would be, just to say that we’ll only eat the food that people offer us. We won’t go out and buy our own food, and so, when I set the monastery up like this, people told me, you are crazy.

We were not in the middle of the town. They said you will starve to death. People will not bring you food. And I said, well, let’s just try it and see what happens. when I arrived here to move in, people had already filled the refrigerator. There was only one time when we had finished the food in the refrigerator, but there was still some canned food. That was the lowest we ever got. Ever since the beginning, we haven’t starved at all.

We don’t charge for the retreats. We depend on the food people bring to see not only the community but all the people who come here to study and meditate with us. They come, and they offer it. I think being generous makes people’s minds happy, and so, doing it this way, people are generous to us.

That enables us to be generous in return. So, we give all the teachings free of charge. It is the economy of generosity.

Sandie Sedgbeer: So, in The Compassionate Kitchen, you talk about intention being the most important aspect of any action and how this relates to our motivation for eating. Can you expand on that for us?

Venerable Thubten Chodron: In Buddhist practice, our intention, our motivation, is what really determines the value of the action that we do. Okay, so, it’s not how we look to others and whether others praise us or blame us. We all know how to act phony and pull the wool over people’s eyes and make them think we’re better than we are, but in Buddhist practice, doing that is not a spiritual practice. Our spiritual development does not depend on people praising us.

It depends on our motivation, our intention. Why are we doing what we do? With this fast-moving world and with our senses always directed outwards towards, the things and people in our environment, we so often don’t really checkup, why am I doing what I’m doing. Generally, we just act on impulse.

So, in spiritual practice, it kind of slows you down, and you have to really think, why am I doing what I’m doing, and so, in terms of eating, we have in the book the five contemplations that we do before we eat. It really helps us set our intention for why we’re eating and the purpose of eating. Then having accepted the food, what our job is to repay the kindness of the people who offered it.

Sandie Sedgbeer: There’s been an explosion of late in interesting cook, in food preparation, in food competitions, food TV programs in the technology of food. Many regards preparing food as a meditative practice, but the motivation, I’m not sure that the motivation, the intention, is the same intention as we’re talking about in The Compassionate Kitchen.

Venerable Thubten Chodron: Yeah. I don’t know other people’s intentions, but I do know that it could be very easy to have the intention of producing something pleasurable, who knows?

But let me just tell you about the five contemplations that we think about before we eat because this really sets the stage for the motivation.

So, the first thing we recite together is “I contemplate all the causes and conditions and the kindness of others, by which I have received this food.”

It is thinking about the causes and conditions of the food, the farmers, the people who transported the food, the people who prepared it, and what we did in our lives to be able to receive the food.

Then to contemplate the kindness of others, to really see, people are going to work every day. They work hard. It’s difficult in modern society, and then out of the goodness of their heart, they share their food with us. So, to really think about that before we eat.

The second one is, “I contemplate my own practice, constantly trying to improve it.”

So, this is really seeing our responsibility, to look at our own spiritual practice and then to try and improve it, to better it as a way of repaying the kindness of other people.

In other words, not just taking food for granted, not just thinking, well, it’s lunchtime.

It’s taking our mind away from all that grasping and self-centered attitude.

The third contemplation is, “I contemplate my mind, cautiously guarding it against wrongdoing, greed, and other defilements.” So, when we’re eating, to eat mindfully, to eat tentatively, to keep our mind free from wrongdoing and greed and other defilements, so, the mind that is always saying, I like this. I don’t like that. There’s not enough protein. There are too many carbs.

The mind is constantly dissatisfied. And so, determining before we eat, we’re not going to give way to that kind of mind, and we’re going to stay in a mind of cultivating contentment with what we have and of appreciation and gratitude.

The fourth contemplation is, “I contemplate this food, treating it as wondrous medicine to nourish my body.”

Continue to Page 3 of the Interview with Venerable Thubten Chodron – The Compassionate Kitchen

A veteran broadcaster, author, and media consultant, Sandie Sedgbeer brings her incisive interviewing style to a brand new series of radio programs, What Is Going OM on OMTimes Radio, showcasing the world’s leading thinkers, scientists, authors, educators and parenting experts whose ideas are at the cutting edge. A professional journalist who cut her teeth in the ultra-competitive world of British newspapers and magazines, Sandie has interviewed a wide range of personalities from authors, scientists, celebrities, spiritual teachers, and politicians.