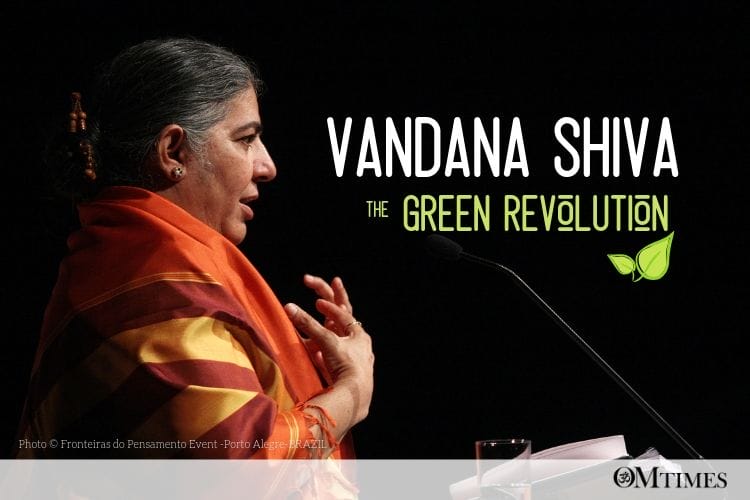

Vandana Shiva: The Green Revolution

Vandana Shiva is an Indian scholar, environmental activist, food sovereignty advocate, alter-globalization author and proponent for a Green Revolution. Vandana Shiva, currently based in Delhi, has authored more than twenty books. She is one of the leaders and board members of the International Forum on Globalization (along with Jerry Mander, Ralph Nader, and Jeremy Rifkin), and a figure of the global solidarity movement known as the alter-globalization movement. She has argued for the wisdom of many traditional practices, that draws upon India’s Vedic heritage. She is a member of the scientific committee of the Fundacion IDEAS, Spain’s Socialist Party’s think tank. She is also a member of the International Organization for a Participatory Society. She received the Right Livelihood Award in 1993, an honor known as an “Alternative Nobel Prize”. Patrick Pittman sits down with her for this interview.

An Interview with Vandana Shiva: When Mother Earth Speaks

Interview by Patrick Pittman

PATRICK PITTMAN: You talk about Climate change, food security, oil supply, the politics of water, biotech—when considered separately, these issues seem too vast to tackle in a single life or body of work, but is there something unifying that defines a mission for you across all of it?

VANDANA SHIVA: Well, I see a deep connection between climate change and agriculture. At least forty percent of greenhouse gas emissions are coming from agriculture, and agriculture is most vulnerable to the impact of climate instability. We are witnessing it in India right now and in the United States. The solution to climate problems of instability and predictability, as well as the food crisis, is ecological agriculture. Feed the soil with organic matter; it’ll allow you to go through a drought. It’ll also reduce emissions. It’ll give you more food.

The seed is not just a source of life. It is the very foundation of our being. Vandana Shiva

PATRICK PITTMAN: Amongst all of your work, across all of these issues, in the end, it comes back to a consistent solution of seed-to-soil food production.

VANDANA SHIVA: Yes. You know, at the basis of all of this is a certain kind of thinking- Mechanistic thinking. The idea that the world is a machine, and you could break it down and fix it back and everything will go on. Linked to that is a particular idea of the economy—that it must be industrial, that it depends on fossil fuels. Now, there are hundreds of ways to produce; humanity existed long before fossil fuels came into our economy, and growth is a mismeasure. All it does measure is how fast you can destroy your natural endowments; how fast you can destroy your society to commodify and commercialize. That growth train eventually stops; we’ve seen it stop in Europe; we’ve seen it stop in the US. Brazil, India, and China were kept up as the poster children for growth. The BRICs. We were turned into bricks! We were called ‘emerging countries. Now we’re grinding to a halt! In Brazil, there’s only two percent growth. In India, five percent. So, this whole ‘making growth the objective,’ which is nothing but the destruction of society and nature, it must end.

PATRICK PITTMAN: To reclaim sanity, you begin with what is available to you. You can’t change the minds of those who become billionaires.

VANDANA SHIVA: You can’t change the minds of governments who think this is the way to go. You begin with your back yard. You begin with the pot on your balcony.

PATRICK PITTMAN: You were trained as a physicist, but you’re a long way from that these days. Was there a moment of awakening, or were you always fighting?

VANDANA SHIVA: Well, you know, I became a physicist A, because I wanted to understand the world, and, B, Einstein was my inspiration. I went to a school where they didn’t teach physics, but I found ways to learn physics, and eventually went into the foundations of quantum theory. I didn’t stop doing that work because it bored me; I didn’t stop doing that work because I’d had enough. If I moved out of my preoccupation with the foundations of quantum theory, which I thoroughly enjoyed, it was really for two reasons. I’d become involved with the Chipko movement while I was a student. So, I hadn’t given up physics at that time. But, as a result of doing ecology on the side, working with movements, every vacation for me was a vacation where I participated in and volunteered with movements like Chipko. At the end of it I was writing a lot and doing studies for fun, and hobby, and service. Those started to create this identity of me as a so-called ‘environmental expert,’ and the government started to commission studies, and those studies turned into saving entire ecosystems.

PATRICK PITTMAN: What was your first encounter with the women of the Chipko movement?

VANDANA SHIVA: I call them my ‘university of ecology.’ I was going off to Canada, and I wanted to visit some of my favorite spots. My father had been a forester and had walked and trekked this area. I had a few days before I was going to catch the flight and I thought, I’ll just walk this mountain, sit in the stream, and take these memories with me. I just wanted to take something precious with me. And the mountain forest was gone, and the river was a trickle, and I couldn’t swim in it. I’m coming back; I’m sitting and talking to the local villagers and saying, ‘My God, this has been a disaster.’ And then they informed me and said, ‘Yeah, but it’s going to stop.’

In a village hundreds of miles away, women had started acting, and they’d started the Chipko movement. My connection to Chipko came from my personal experience of deep ecological loss. Of course, later, when I started to make connections, I realized every one of the activists who were supporting the movement was all friends of my parents. A boy who used to come and sing for my mother, who used to come and visit our place. So, then a second connection was made. But at that time, I was too young. And I didn’t know that over time this would become a connection with a movement.

PATRICK PITTMAN: Were your Parents activists?

VANDANA SHIVA: My mother, for sure, yes. Very much an activist. My father was an ecologist; you know, he was in a government job, but his heart was very much in these issues. My mother had given up official work and became a farmer and was much freer. Wherever my father got posted, she would seek out the best poets, the best activists, the best social workers, it was wonderful. So those were the kind of people who surrounded us as we were growing up.

PATRICK PITTMAN: Were you raised in some way to believe that the game around you was rigged and that you had to fight it?

VANDANA SHIVA: Well, we didn’t know the larger game. We just knew the game of truth. We knew the game of simplicity. We didn’t know the larger game because we weren’t in it. Our parents weren’t in it; my father was a forester, we lived in the forest. I remember, as a teenager saying, ‘Oh, you know, we come to the forest, all my friends go to discos.’ He said, ‘You want to go to the disco? Come! Get into the car!’ He drove us to Delhi. We go into this dingy basement. After five minutes I say, ‘Oh my God, this is so boring. The forest is so much more exciting!’ [Laughs].

So anyway, the rigged world, I got into it bit by bit. My own intellectual life was very innocent as a physicist. I often say I found the world behind the eucalyptus tree!

I didn’t know there was something called the World Bank until I started to see all the areas around Bangalore turning into eucalyptus monoculture. I asked, ‘Why is everyone planting eucalyptus?’ I can’t live with unanswered questions, you know. That’s the scientist in me. If I find a question mark, I’ve got to answer it! So, there was this big question mark: ‘Why is every farmer planting eucalyptus?’ I started to do the study and found a World Bank loan behind it. That’s when I found out about the World Bank. Then I studied the World Bank. Then I thought we’d dealt with the World Bank; we were going to be at peace. Then they created the World Trade Organization.

PATRICK PITTMAN: Now you’re often referred to, even on your book blurbs, as a “radical” scientist. It always strikes me as interesting when people preaching very traditional and old ways of engaging with the earth refer to themselves as “radical.” But what does it mean to you to be radical in science?

Continue to Page 2 of the Interview with Vandana Shiva

OMTimes Magazine is one of the leading on-line content providers of positivity, wellness and personal empowerment. OMTimes Magazine - Co-Creating a More Conscious Reality