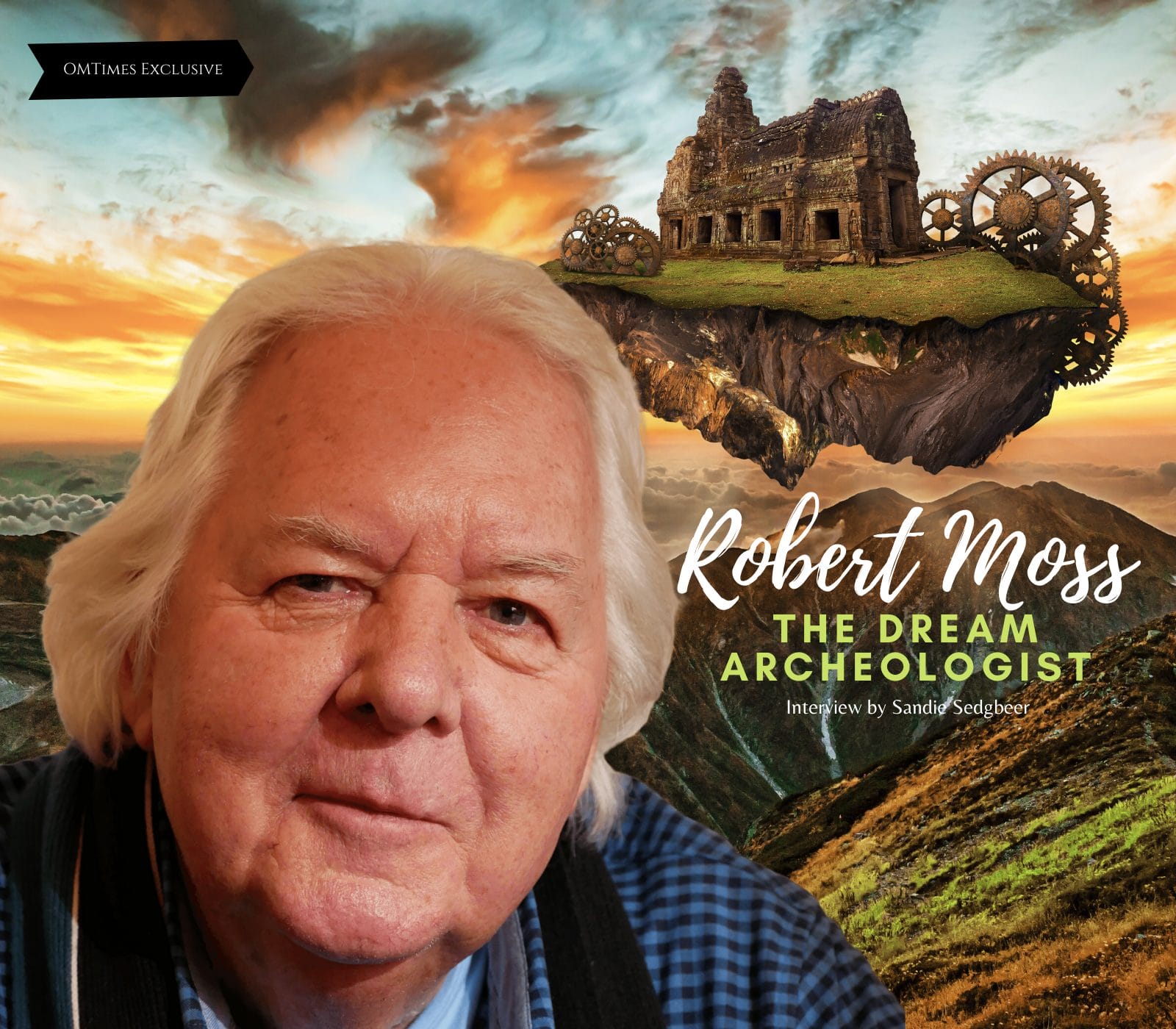

Robert Moss: The Dream Archeologist

Robert Moss is a Dream Traveler, a former lecturer of ancient history at the Australian National University, a New York Times bestselling novelist, poet, journalist, and independent scholar who leads popular workshops all over the world. He is the creator of the School of Active Dreaming, a three-year training program for teachers of Active Dreaming.

An Interview with Robert Moss: The Dream Archeologist

Interview by Sandie Sedgbeer

To listen to the full interview of Robert Moss by Sandie Sedgbeer from the radio show What Is Going OM on OMTimes Radio, click the player below.

I am not just talking about analyzing symbols from a dream but bringing the dream into life. I am talking about seeing the world around you as a waking dream where the symbols and synchronicities will speak to you if you pay attention. That is why I call it active dreaming because it is about getting active with all our dreams can be. Robert Moss

Robert Moss has been a dream traveler since doctors pronounced him clinically dead when he was just three years old. From his experiences in many worlds, he created his School of Active Dreaming—his original synthesis of modern dreamwork and ancient Shamanic and mystical practices for journeying into realms beyond the physical. A former lecturer in ancient history at the Australian National University, a New York Times bestselling novelist, poet, journalist, and independent scholar, he leads popular workshops all over the world, including a three-year training for teachers of Active Dreaming.

Robert Moss joined Sandie Sedgbeer in a conversation about his extraordinary life experiences, his work, his dream travels, and two of his many books on dreaming, shamanism, and imagination—The Boy Who Died and Came Back and Dreaming the Soul Back Home.

Sandie Sedgbeer: Robert Moss, welcome!

The title of your spiritual memoir The Boy Who Died and Came Back: Adventures of a Dream Archaeologist in the Multiverse, derives from what the doctor said to your parents when you first died in this lifetime. Tell us about that experience.

ROBERT MOSS: I was three years old, and my mother took me from Melbourne to Perth, where her family lived to meet my great aunt. Her aunt was the famous Opera Singer, Dame Nellie Melba’s understudy and friend, and a very influential medium, though she kept that quiet. Auntie Dick, as we called her, read my “tea leaves” in an old-fashioned way, and though she didn’t tell us till much later, she saw my death that winter in Tasmania. My father was in the army and was transferred down there. I was pronounced clinically dead after a bout of pneumonia in the hospital. Then I revived, and the doctor said to my mother—I think with some embarrassment—’Oh, your boy died, and he came back, didn’t he dear?’

So, that was the start of it. I don’t remember anything much, but I do know it was tough to operate my body. I was born a big, sturdy, strong, outdoor type of Aussie, and then I was very sick and much alone in sick rooms, which gave me a life of the imagination, a life of dreaming.

Then, at nine, I said to my father, I feel a bit crook. He calls an ambulance as he knows I don’t complain. My appendix was about to blow up. I’m under emergency surgery, and I’m out of my body. This starts to sound like one of those familiar ND experiences, but it goes a bit further. I’m nine years old, in a Melbourne hospital room, and I’m looking at my body from under the ceiling, and I don’t like seeing the body being cut open. So, I wander out into the corridor in my second body, my dream body, and there’s my mother sobbing, and I feel guilty. I’m an only child, and I don’t want to be around her pain, as I’m sorry for causing it. I look through the window in my second body, and the sun’s out, there’s the beach, and there’s Luna Park, the famous Australian theme park, and I want to get out along the beach and go to the theme park.

So, I’m suddenly recording the fact that my body is actually on an operating table. I’m out of the hospital, entering the Moon Gate of Lunar Park, and it’s a bit creepy, but I’m having fun. I get on the Ghost Train, and I’m going down and, suddenly, bang, I’m in another world. I don’t understand this, I’m simply there, and I’m receiving love by beautiful people who seem taller and paler than a regular human. Still, it never occurs to me that they’re different. I’m loved there, I’m received there, and I seem to live a whole life with these people. I mean, they feed me, raise me, train me to be some kind of Shaman of their culture, and I seem to live a full life. I become a father, grandfather, elder, have children and grandchildren. That body is tired and used up, and I think I’m going to fly to another star and, suddenly, bang, I’m back in the body of a frightened nine-year-old boy in a Melbourne hospital operating room, and I remember.

Now, this created a huge problem because I came from a military family in a very conservative era in Australia, and they wanted to support me. Still, they can’t understand what I’m saying. The doctor’s saying it’s the medication, ‘he’s hallucinating poor kid.’

The first person I meet who can understand what I went through and am now going through because now I can see across time and talk to the dead, and dreaming, is an aboriginal kid, who I’m not supposed to hang out with as it’s a racist era. But my aboriginal friend, when he hears my stories, is a matter of fact. “Yes, we do that. We get sick, and sometimes we go live with the spirits, don’t we? We come back sometimes the same and sometimes different.” And he says, “My uncle, the artist, does that to get ideas for his good paintings, the stuff that’s not for the tourists. The real stuff.”

So, I’m learning from someone from the first peoples of my native country that dreaming can take you into the dream time. It can take you to a deeper place, to another reality, and to the ancestors who are something beyond the ancestors of your bloodlines.

That is actually the root of my engagement with dreaming all of my life. I’ve done different things in my life, but I’ve only really screwed up when I’ve stopped listening to my dreams. So, I carried that from my childhood and, of course, added to it the curiosity of an independent scholar and the practice of a shamanic dreamer.

I’ve learned many important things about dreaming that are more essential in modern life right now than they’ve been for generations. I’ve learned that dreaming is about survival, that it shows us the roads in life that we are following, and rehearses the challenges and opportunities around us. I’ve learned that dreaming is about the soul. It puts us in touch with our authentic spiritual teachers. It reminds us of our spiritual purpose and, frankly, in these pandemic times, dreams also are about fun stuff, like we can travel without leaving home. We don’t have to keep a social distance. We can be as close to people we want to be with as many people as we like. Dreaming is about traveling, about entering deeper realities, and about remembering what the soul wants. This is the basic knowledge I’ve carried from childhood, and I think a lot of people are hungry, actually, for this kind of access.

SANDRA SEDGBEERYou had a very lonely childhood and plenty of opportunities to travel inside and elsewhere. Still, later in your life, some of the experiences you had with dreaming became the substance of your best-selling novels, didn’t they?

ROBERT MOSS: I use them in my novels. My characters have dreams, and the dreams are reported, and some of my dreams guided plot turns and narratives. My novels are basically thrillers and mysteries, but I found my dreams gave me themes, they gave me characters, they gave me plot resolution, and then, of course, a moment came when I had to go beyond that phase of my life. I was living on a farm in Upstate New York, which I’d been guided to by an amazing series of synchronicities. I bought the place because of the waking dream. I was thinking I’d like to get out in the country. I’d like to put down some roots in my adopted country. I was fed up with the fast track in New York that I’d been on. So, I’m looking at a dilapidated farmhouse on some land in the upper Hudson Valley of New York, in traditional Mohawk Indian country. I’m sitting under a 400-year-old wild oak tree that had survived the lightning, and suddenly I hear a squalling sound above me. Crrrwww. Crrrwwww. I look up, and a red-tailed hawk is circling above me, dropping lower and lower. Squalling at me in a language I feel I ought to be able to understand, and she – I learned later it was a she because of her size – dropped a feather between my legs. It’s not the only reason I moved to the farm, but it’s one of the reasons.

Continue to Page 2 of the Interview with Robert Moss

A veteran broadcaster, author, and media consultant, Sandie Sedgbeer brings her incisive interviewing style to a brand new series of radio programs, What Is Going OM on OMTimes Radio, showcasing the world’s leading thinkers, scientists, authors, educators and parenting experts whose ideas are at the cutting edge. A professional journalist who cut her teeth in the ultra-competitive world of British newspapers and magazines, Sandie has interviewed a wide range of personalities from authors, scientists, celebrities, spiritual teachers, and politicians.