Call of the Ganges – Hollywood to the Himalayas

Rishikesh is laid out on two sides of the Ganges (correctly, Ganga) River, a bustling downtown on the western side and a quieter area on the eastern side.

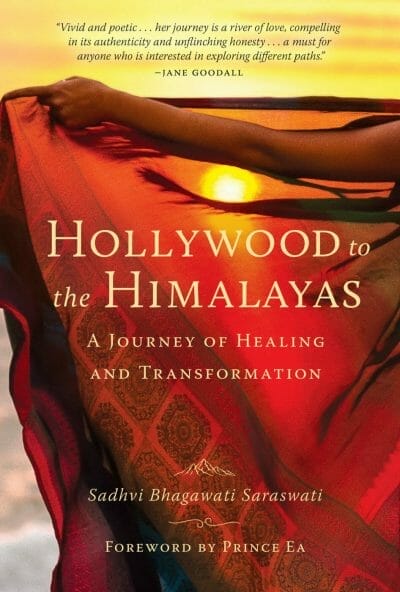

An Excerpt from Hollywood to the Himalayas: A Journey of Healing and Transformation

Written by Sadhvi Bhagawati Saraswati

The southeastern quarter centers itself near Ram Jhula, a swinging footbridge named after Lord Rama, the divine hero of the Ramayana, while the northern part is centered around Lakshman Jhula, a similar bridge named after Lord Rama’s brother, Lakshman. Lakshman Jhula is where most of the hotels, shops, and restaurants for tourists are. The Ram Jhula area, also known as the Swargashram (literally, Heavenly Abode) area, is lined with ashrams.

In September 1996, the Green Hotel was the only hotel in the Swargashram area of Rishikesh, sitting on a small lane that runs parallel to the Ganga, just behind the ashrams. Of course, Lonely Planet did not mention that in order to reach there, you have to schlep your bags across a nearly half-mile-long footbridge. So, when we arrived at the Ram Jhula taxi stand to discover that our hotel was across the water, the driver instructed helpfully, “You cross bridge.” No mention of the large, convenient motorboat that pilgrims can use to travel easily from bank to bank of the river, no offer to find a coolie—the driver simply pointed his finger toward the swinging footbridge, more than 300 yards past where he had to drop us off.

You couldn’t find a hotel that doesn’t require schlepping our bags across a river? I berated myself as we found ourselves sharing a bridge, barely two feet wide and precariously suspended a hundred feet above water, with stray cows, sugarcane-laden bullock carts, fruit and vegetable vendors, motorcyclists, and two-way foot traffic. I was sure we had walked onto the set of the Indian version of The Bridge of San Luis Rey. Finally, hot, sweaty, and already done with India, I followed Jim through the doors of the Green Hotel.

“How do you get back to the river?” I asked the clerk after we’d checked in and dropped our backpacks in the sparsely furnished room. The Ganga called me. As we had crossed Ram Jhula, our luggage strapped to our backs, the river flowed quickly and deeply below. Each year in the monsoon, the water level rises tens of feet and her springtime gentle flow becomes a rush of summer waves. By mid-September, the rains subside. A brief afternoon storm in Delhi was our only experience of the tail end of the monsoon. However, the Ganga was still brimming from mountain rains and melting glaciers.

The hotel clerk directed me down a narrow alley that ran in front of the hotel between two large ashrams until it dead-ended at a small road lined with tea stalls on the banks of the river. I did not want tea, however, or any of the jewelry or religious statues for sale in the marketplace. I wanted to put my feet in the river. After walking upstream along the riverbank a few hundred feet, I found clean marbled steps leading down to the river.

Pilgrims gathered on the lowest steps, pouring water over their heads from small brass pots or grasping tightly onto chains while they dipped themselves once, twice, thrice in the rushing river. Parents held their naked children close to their chests, scooped up water, and let it drip through their fingers over their children’s bodies. Rubbing the holy water onto their own and their children’s heads, backs, stomachs, and legs, they chanted “Jai Gange!” “Jai Gange!” (Glory to Mother Ganga), and the children squealed. At the far end of the long row of steps sat some meditators with malas (strings of beads) in their fingers, palms open on their knees.

As I walked down the marble steps to the river, I eyed a spot slightly downstream, far enough from the bathers to protect me from their splashing children. I stood, staring at the flowing water and at the dark green mountains on the opposite bank.

And then it happened—an experience that twenty-five years later, I still struggle to articulate. From the landscape of river, mountains, steps, and bathers came an image of the Divine. Woven into and out of the treads of my visual field, occupying every frame of perception, out of the light and colors and shapes and hues and textures of the world I had been watching came a divine form, an image of divinity that blended into and yet stayed distinct from the background.

The next thing I knew, I was seated on the steps without remembering how I went from standing to sitting. I was sobbing, breathless, yet with no experience of either the sadness or happiness that typically accompanies tears. The tears were not foreign or external, not due to some effect or impact. Rather, they were myself flowing out of myself as the waters of Ganga flowed by my feet. Waves of water outside and waves inside.

The image of the goddess Ganga formed out of every color, shape, texture, and aspect of my visual spectrum. Here She was. And here I was. Yet, it wasn’t really a Her; rather, it was an All, an Everything. And I, I was part of that Everything. There was nowhere I ended and All began. There was nowhere She wasn’t. I stared—eyes open into Her form over the flowing river. I had come home.

I sat on the cool marble steps, crying into the river. They were tears without thought, not the type I usually cried. These tears were not connected to any idea or memory or anything someone had said or done. They were simply tears of being in the presence of truth.

Minutes, hours, days, and lifetimes passed while I sat beside Ganga’s flowing waters. My mind had become nonverbal. The only thought that arose periodically was, Oh, my God. It came not as an intellectual thought but as an outburst. Oh, my God, it is amazing! Oh, my God, it is so beautiful!<

As I shifted my eyes from the river to the families on her banks, to the marble steps, the background of my visual field changed—first, flowing water, then, bouncing children and pious parents, then, the inanimate structure of the steps. My visual field had become split into foreground and background. The background changed based on where I looked and what I was looking at: a person, a pillar, a rock, a statue. But the image of the Divine stayed as the foreground of my visual field and did not change. Whatever I saw—a child, a mother, a marble pillar—I cried. Each varying background was the undulating canvas of color and energy on which the Divine was painted.

At some point, Jim came down. “Hey,” he said in words I no longer understood. “Pretty beautiful, no?” My mind was still nonverbal—all senses and awareness and knowledge had dissolved like salt dolls into the watery soup of my consciousness. I was unable to tease apart the various ingredients from the rest of the soup. Words, too, blended into the soup, unable to be extricated. I looked at him and cried as I smiled.

“Wow,” he said as the tears poured out of my eyes, onto my clothes, and onto the marble steps between us. He sat down quietly next to me.

To learn more, or to purchase Hollywood to the Himalayas, click the book cover or visit Amazon.com

All proceeds from the book will be donated to the Divine Shakti Foundation, a charitable organization dedicated to women, girls, and education.

Learn more about getting your book, product, or event featured in an OMTimes Spotlight!

About Sadhviji

SADHVI BHAGAWATI SARASWATI serves as on the United Nations Advisory Council on Religion and on the steering committees of the International Partnership for Religion and Sustainable Development (PaRD) and the Moral Imperative to End Extreme Poverty, a campaign by the United Nations and World Bank. She is also the Secretary-General of the Global Interfaith WASH Alliance, an international interfaith organization dedicated to clean water, sanitation, and hygiene; president of Divine Shakti Foundation, a foundation that runs free schools, vocational training programs, and empowerment programs; and director of the world-famous International Yoga Festival at Parmarth Niketan Ashram, Rishikesh—which has been covered in Time, CNN, the New York Times and other prestigious publications and has been noted by both the Prime Minister and Vice President of India. Sadhvi has lived for the past 25 years at the Parmarth Niketan ashram in Rishikesh, India, where she oversees a variety of humanitarian projects, teaches meditation, lectures, writes, counsels individuals and families, and serves as a unique female voice of spiritual leadership throughout India and the world.

OMTimes is the first and only Spiritually Conscious Magazine. Follow Us On Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Linkedin, Pinterest, and Youtube

OMTimes Magazine is one of the leading on-line content providers of positivity, wellness and personal empowerment. OMTimes Magazine - Co-Creating a More Conscious Reality